Building Community

Eulenspiegel Puppet Theatre is a nonprofit, tax-exempt puppet company organized to promote the art of puppetry by producing and presenting high-quality performances and workshops. The company is committed to educating the public about the art of puppetry and enhancing the quality of community life.

In 1989, after fifteen years of touring, we became a nonprofit, tax-exempt 501c3 company. Our contact person at the Iowa Arts Council had been urging us to stop applying for grants through the umbrella of our local arts council and take this step.

“Granting organizations will take you more seriously if you have your own tax-exempt status. It will open lots of doors for you,” she said.

The IRS designation changed us and our puppet company in ways I never imagined. We began to feel responsible for contributing to the common good. We’d been producing performances and workshops and educating for years. Now it was time to start “enhancing the quality of community life.” At the suggestion of an art teacher on our Board, we decided to start by creating a “Young Puppeteers Festival,” open to anyone in third grade and above—-adults included—who was young to the art of puppetry.

We contacted teachers and scout leaders, and sent news releases inviting the general public to create 15-minute puppet shows. We offered a free consultation on writing, puppet building, or performance to any person or group who signed up. We asked a magician friend to act as emcee and do magic tricks between acts. We asked theatre friends to form a critique panel. Our board members helped us assemble packets for each participant, and the Iowa City Library agreed to let us convert their largest meeting room into a theater.

Ten groups signed up. My late puppet partner, Teri Jean Breitbach, and I took turns doing consultations: starting groups on the puppet-making process, introducing them to different styles of puppets, helping them understand how writing for puppets is different from writing for people, and even attending and critiquing their rehearsals.

Saturday, May 2, 1992, was the big day! Our board gathered and helped us set up lights, sound equipment, and a portable backdrop. We picked up donated cups, napkins, snacks, and drinks, and set up tables and chairs. We commandeered a smaller meeting room for the critique panel. Our emcee greeted the large audience, and the first Young Puppeteers Festival began!

Anticipation filled the air. Most groups had brought their own staging, designed to accommodate the show and style of puppet they’d created. A few used our generic hand and shadow puppet stages. After each group finished, they moved to another room to meet with the critique panel. Critiques were succinct, encouraging, and completed during set-ups and strikes.

Each young puppeteer received a mini-conference packet with a program, coupons for local shops and restaurants, and the makings of a simple paper puppet. In the mid-afternoon, we took a break so everyone could assemble and show off their puppets.

The show I remember best from that first year was a shadow puppet show created by a group of 4th through 8th graders from Willowwind, a small alternative school in Iowa City. They told the story of Rosa Parks, showing a bus full of people. Rosa Parks was a solid black silhouette, while the white passengers had faces cut out to create a black outline with a white center.

Monica Leo

The Festival lasted ten years before it became too time-consuming to manage. The good news: it’s coming back this year under the able management of our Outreach Director, Chris Eck.

In 1995, we bought a run-down storefront in West Liberty. My late husband John Jenks, a carpenter, brought it back from wrack and ruin to create Owl Glass Puppetry Center. Now that we had a specific community, we looked for ways to tailor our outreach activities to this particular place. We looked to the North, to our friends at In the Heart of the Beast Puppet and Mask Theater in Minneapolis for inspiration. We knew they invited their community to help build giant puppets for an annual May Day parade. We had heard that the county fair parade was a big deal in West Liberty, so we decided to build four giant puppets, and invite local kids to help us and join us in the parade. A local TAG (Gifted and Talented) teacher sent us a few kids, and before we knew it, the word had gotten out among the neighborhood kids too. We were flooded!

West Liberty is about 50% Latino, with lots of new immigrants who live in the downtown apartments near the puppetry center. In those days, there were minimal summer activities for low-income kids, so Owl Glass became the hub. As soon as we opened the doors each morning, scores of eleven- and twelve-year-old boys poured in with their four- and five-year-old siblings in tow. I would show the first batch of kids what to do, and they had to instruct the ones who came later in the day. The place hummed with activity. Kids worked on the giant puppets, but they also made their own smaller creations. Whenever someone started acting up instead of working, I’d say, “You're done for today. See you tomorrow!”

On Parade Day, they all showed up to join our group.

Monica Leo / The kids who made puppets with us and rode with them in the parade. See the front row clutching the trophy we won?

Monica Leo

After a few years, organized summer recreation activities and the trend toward helicopter parenting took over. We couldn’t just send kids home anymore; we had to wait for parents to pick them up. Although I miss the joyous chaos, the smaller groups we attract are much easier to manage, and our parade entries continue to amaze and amuse. This year we will collaborate with a local Latin band to create a float with giant puppets and live music.

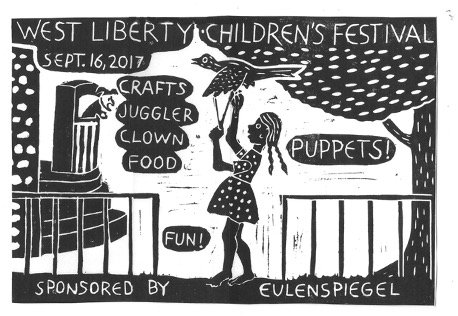

By the time we ended the Young Puppeteers Festival, we had already launched another festival, the West Liberty Children’s Festival, which still takes place every September. This year will be the 25th. The first year, we had $1,600.00 in grant funds. We spent some on publicity, programs, and t-shirts, and the rest on small honoraria for performers. I called in favors from musician and storyteller friends, who agreed to perform for much less than they were worth. We got local clubs and businesses to put up activity booths. The Rotary Club sold hot dogs, brats, and turkey tenderloin sandwiches. The street featured painting stations with easels, a fishpond, a duck pond activity, and a giant sandbox. Enough people showed up and enjoyed themselves to warrant a repeat the following year.

I made a linoleum block printed poster—like the ones I made for our shows—and the image, a little girl with pigtails doing a cartwheel, appeared on the t-shirts and all of the publicity materials. That little pig-tailed girl has been on every festival poster and t-shirt since. Sometimes she’s working a puppet, sometimes watching a show, cheering, or blowing bubbles. In 2021, she wore a pandemic face mask.

Monica Leo

After the first festival in 1998, it took a few years before the town got seriously involved. Year by year, involvement grew, until year ten, when a local mover and shaker approached me.

“Monica, why don’t you let us do your fundraising for you? We can suck a lot more money out of these people than you can.”

Monica Leo

The following year, our budget tripled, and we could pay our performers and even bring in guest puppeteers from other states! We added musicians and a juggler to the street. We had face painters and a balloon-twisting clown. Bit by bit, the West Liberty Children’s Festival also became a mini puppetry festival. In addition to thousands of local and area residents, it began to attract puppeteers, who came to see their peers perform. We added a Friday night puppet slam for adults, and asked our guest puppeteers to bring content. Eventually, we even added a few Friday workshops, open to local residents and visiting puppeteers.

In 2016, we began collaborating with Latinos Unidos, a local nonprofit organizing an annual Latino festival with Latin bands, a Mexican market, and taco trucks. Nowadays, the Children’s Festival goes from 10:00 to 3:00 while the Latino Festival takes over from 3:00 to 10:00. We share the food vendors, the porta-potties, and the Mexican market. Together we set up the street, get the necessary permission from the city, and clean up at day’s end.

Our festival has become one of West Liberty’s major annual events.

In the late ’90s, we became friends with the local Lutheran minister, Terry Mahnke. After 9/11, he stopped over, and we discussed the community response to the terrorist attack. We agreed that working on a creative community project would be a positive step, and Terry immediately proposed a community puppet show. The Iowa Arts Council offered a grant for projects addressing the tragedy of 9/11. Our project was chosen for funding. It was full speed ahead

Puppets and People For Peace began to shape up. We looked for stories that featured people working together and discovered a Native American tale, “Pushing Up the Sky.” It was a creation myth, telling how earth and sky became separate. It featured an entire village working together to push up the sky. We envisioned it as a shadow puppet show with a large round shadow screen. With the help of our community, we crafted stark images with colored accents, showing animals, humans, and constellations.

Our friend Bob Aiken, a former Iowa puppeteer who’d moved to Colorado, came for a week to teach The Circle of Creation, a show he had created to fit our theme.

We decided to start and end with a parade of giant puppets into and out of the theater. We made a sun and a moon, each about ten feet tall, and lined their fabric bodies with battery-operated twinkle lights. We made a twelve-foot Mother Earth character. Her cloth body was composed of a patchwork of every kind of ethnic fabric we could find. Her face became a collage of many faces of all different skin colors. Our elementary art teacher worked with her second graders to create the faces in the collage. Each child chose a piece of paper closest to their skin color and made a self-portrait. We cut them out and glued them onto the puppet’s head.

The three giant puppets marched into the theater to music, an impromptu jam session by musician friends who’d agreed to add their talents to our extravaganza. The puppets perched in stands flanking the puppet stages, our large circular shadow stage, and Bob’s larger frame stage. With our cast of ten, who had spent a week’s evenings rehearsing with us, we performed The Circle of Creation followed by Pushing Up the Sky. We ended by marching the sun, moon, and Mother Earth back out of the theater, in front of a large and enthusiastic audience.

Since that first year, community shows have become an almost annual event. Participants include people from all walks of life: a school superintendent, the chief of police, a Spanish exchange teacher, a plumber and his young son, two mayors, a phys ed teacher, a lawyer, and children and adults of all ages.

Eventually, we started designing the shows we liked the best for touring. We take our favorites—Portraits of the Prairie, Immigrant Stew at the Chat ’n’ Chew, John Brown’s Journey, Five Suns of the Aztecs, The Flea, Don Quixote, and Remembering Buxton—to other towns. Local sponsors organize a cast and crew, and then we arrive, set up the stage and puppets, and rehearse with them. Our collaborating musician comes in for a dress rehearsal and performance. This is one of my favorite parts of my job. I love the energy generated as people discover the power of puppetry for the first time.

In the late 90s, a West Liberty friend suggested we organize a local arts council.

“We have an active arts organization,” she said (meaning us). We should have an arts council.

The West Liberty Area Arts Council (WLAAC, pronounced we-lack) was formed, and members began teaching art classes for adults. The first class was a drawing class, taught by a popular retired art teacher whose numerous friends signed up to lend support. Much to their surprise, several of them discovered an unknown talent and became accomplished practicing artists who sell their work in the Brick Street Gallery, created and maintained by the arts council.

These days, WLAAC sponsors classes, maintains the gallery, hosts a Plein Air painting event, and organizes four evenings bringing live music to our downtown park.

Monica Leo

Recently, I received a thank you card for a donation I’d made. It thanked me for “being the vanguard in bringing the arts to West Liberty” and “for attracting other artists to our town.” It made me realize, once again, the power of building community.