Concrete Cultural Reversals

Rather than thinking on a scale of seconds, days, months, we should extend our time horizons to encompass decades, centuries, and millennia. Only then would we be able to truly respect and honor the generations to come.

—Roman Krznaric

The Good Ancestor: A Radical Prescription For Long-Term Thinking

How does your work heal, reduce harm to, or regenerate relationships with the ecological conditions necessary for human and other than human species to survive and thrive?

How does your work participate in cycles longer than three to four generations?

How does your work contribute to the reversal of the negative consequences of contemporary society’s reliance on fossil fuels and the industrialization of everything?

Concrete Cultural Reversals

I reflect on these questions regularly. They are a distillation of nearly three decades of work as an artist, activist, environmentalist, publisher, and since 2019, a professional composter too. I have lost interest in art and culture that does not address or seek to reverse the multiple ills our society suffers from, particularly those related to climate breakdown.

Protesters demonstrating against government inaction addressing climate chaos have used the phrase “We Are Not Defending Nature, We Are Nature Defending Itself!” I like this and think I understand what they are trying to convey. However, I wish this romantic narrative was even close to being true. Instead, I find myself a petro-being living in a petroleum space-time continuum that constantly distorts every relationship I have to time, place, natural cycles, and life in general. [1] This debased state is where I work from. To make any kind of positive impact, I have no other choice but to trudge through all the contradictions and compromises it posits. It will take generations after the end of fossil fuel use to remove the habitual modes of thinking and acting petroleum has inculcated in each person whose life is defined by its use. These relationships thoroughly suffuse daily life and delimit imagining futures that reduce the collective harmful impact of industrial society.

It has been seven years since I lived in a safe leftist community in a large city. Now, I have a house and family in a place dominated by right wing theocratic conservatism and cynical systems set up to retain an unrepresentative super majority—also called Indiana. We returned so our small children could be around their extended family. I feel it is more urgent and necessary to be working here in Fort Wayne than in the safe places I used to call home.

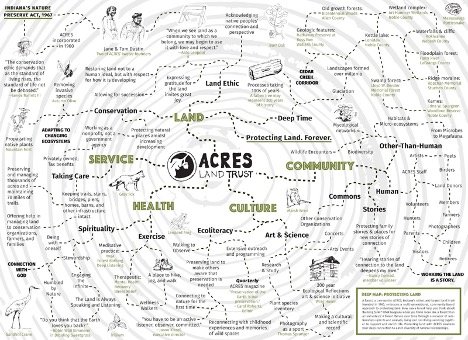

There are many groups and organizations here in NE Indiana that push back against the perils of consumer society and endless economic growth. Shortly after moving back to Indiana from Copenhagen, Denmark, with Bonnie Fortune Bloom and our two daughters, we began collaborating with ACRES Land Trust, an organization dedicated to “Protecting land forever.” The simple act of protecting land has cascading effects. We spent a year interviewing people involved with various aspects of ACRES and made the deep map pictured here.[2] The work of ACRES brings people of varying political, environmental, and religious concerns together at a time when our democratic structures are failing to protect everyone and our planet. Divisiveness threatens the existence of our social order in terrifying ways, but building organizations like ACRES works on this problem and helps mitigate climate change.

Deep map of ACRES Land Trust by Bonnie Fortune Bloom and Brett Bloom

ACRES preserves over 7,000 acres of various types of glaciated terrain and habitat. Some, like the magical mari flats, which have highly alkaline soils, are nearly extinct, as are the oak continuums, largely destroyed by the introduction of private property by colonizers who broke up and fenced off important ecosystems. ACRES understands the need to build cultural support around the act of protecting land. One highly ambitious project is their 200-year-long artist in residency program. They describe it thusly: ACRES’ Ecological Reflections project will fund robust scientific research and commission art and humanities through 2217. As we amass 200 years of science, artwork and writings on Wing Haven [a nature preserve founded by an artist and former teacher at the Art Institute of Chicago in the early 20th century], we will gain insight on how people view their connection to nature, the impacts of land use, and how Indiana’s changing land ethic alters the landscape. [3]

Wing Haven consists of multiple kettle lakes, temperate maple-beech forest, numerous wetlands, and is one of the only sites in the state to house rare and thought to be extinct sedges. Visiting this site teleports you back to another time, an ancient landscape that has all but been destroyed or overdeveloped in the state.

MASSIVE HARM REDUCTION

In the summer of 2019 I started a pilot program for a food scrap composting business in Fort Wayne called Dirt Wain—a wain is an open farm wagon. When people compost, they are reducing their carbon impact in ways that they can feel and sense in their daily lives.[5]We went from composting for 6 households to collecting from hundreds of homes and businesses, processing anywhere from 20-30 tons of compost a month[4]. It will take massive cultural shifts to get everyone composting, which is our goal. We include art, and the work of artists, in the activities of Dirt Wain, to help foster this shift.

Dirt Wain drop-off shed, where people leave buckets full of food scraps and take clean buckets. The shed is made of repurposed materials.

Photo: Tim Zink for Input Fort Wayne, 2019.

Paying someone to offset your carbon enters you into a highly abstract relationship. It does not put the reductions into your direct experience. One of the biggest limits to the thinking behind carbon credits or offsets is that it is not additive. The reduction of your impact does not grow, and you need to pay for more with each new emission. This is the logic of extractive culture and not a real solution. We will not consume our way out of climate breakdown. We need concrete cultural reversals we live with on a daily basis. Reducing the harm we create is something that everyone can start immediately. You can begin with incremental steps, slowly building your impact as you figure out how.

Making things like waste, the true hidden costs of life, and climate chaos tangible is critical for embodied understanding of complex processes that can feel too big and out of reach to grasp. Composting is a direct way to fight climate breakdown, and doing it as a constituent of a cultural force amplifies the feeling of success, which breeds more action. You can fight climate change by protecting land, planting trees, starting small prairies, and creating systems that massively reduce the waste made by yourself and others.

What would it look like if each person figured out a way to massively reduce the ecological impacts that they and their fellow citizens were responsible for? I am not simply talking about schemes like carbon offsets, but things we have and haven’t thought of. Why can’t your art be directed towards this too?

Draft of an illustration by Kione Kochi showing some of the relationships Dirt Wain’s activities set in motion.

Volunteers move mulch and plant 1400 live plugs of 35 native species in the Dirt Wain garden, Summer 2021.

In 2019, Dirt Wain began work on a community and prairie demonstration garden. Last year, we installed over 1400 plugs of 35 species of low stature: all flowering, native prairie plants. We started the garden to offer a public place for gathering, workshops, and various other activities that connect the humble act of composting your own food scraps to larger efforts of healing land and the landscapes that sustain us in our area. Kione Kochi’s illustration gives a sense of some of the things we have done and plan to do at the garden.

Half Letter Press

In addition to the work I do with Dirt Wain and a collaborative artist, I work with Marc Fischer (Chicago) in the art group Temporary Services, which we started with Salem Collo-Julin in 1998. In 2008, we began a publishing imprint called Half Letter Press. Since starting Temporary Services, we have made over 120 publications, including Book Waste Book (2022), which looks at all the waste it takes to make a publication. Each edition includes two multi-color RISO-printed sheets upcycled from Half Letter’s waste stream.

Half Letter Press

While conducting research and writing that book, Marc and I came across several accounts of how much water it takes to make a single sheet of paper. We were alarmed that it could take up to 3 gallons to make just one, and we wanted to do something to offset this waste. We both installed dual-flush, low water toilets in our homes. In the first year of use, we will more than offset the amount of water used to make the publication, and this offset will continue to add even more water savings through continued use. This way of offsetting is additive. We will pay to offset the water use of all our subsequent publications. We have a publication in the works now and will install another toilet to offset its hidden waste water.

We are in the early stages of developing a service where artist publishers and independent bookstores can help offset the hidden waste water in publishing. We hope to offer the ability to purchase water credits in the form of dual-flush water-saving toilets. These toilets can be installed in publishers’ houses, or can be donated to others who will help in the process. I mention this initiative because it is one that can massively reduce the impact people have when they make publications, and it is a process that keeps adding to the savings.

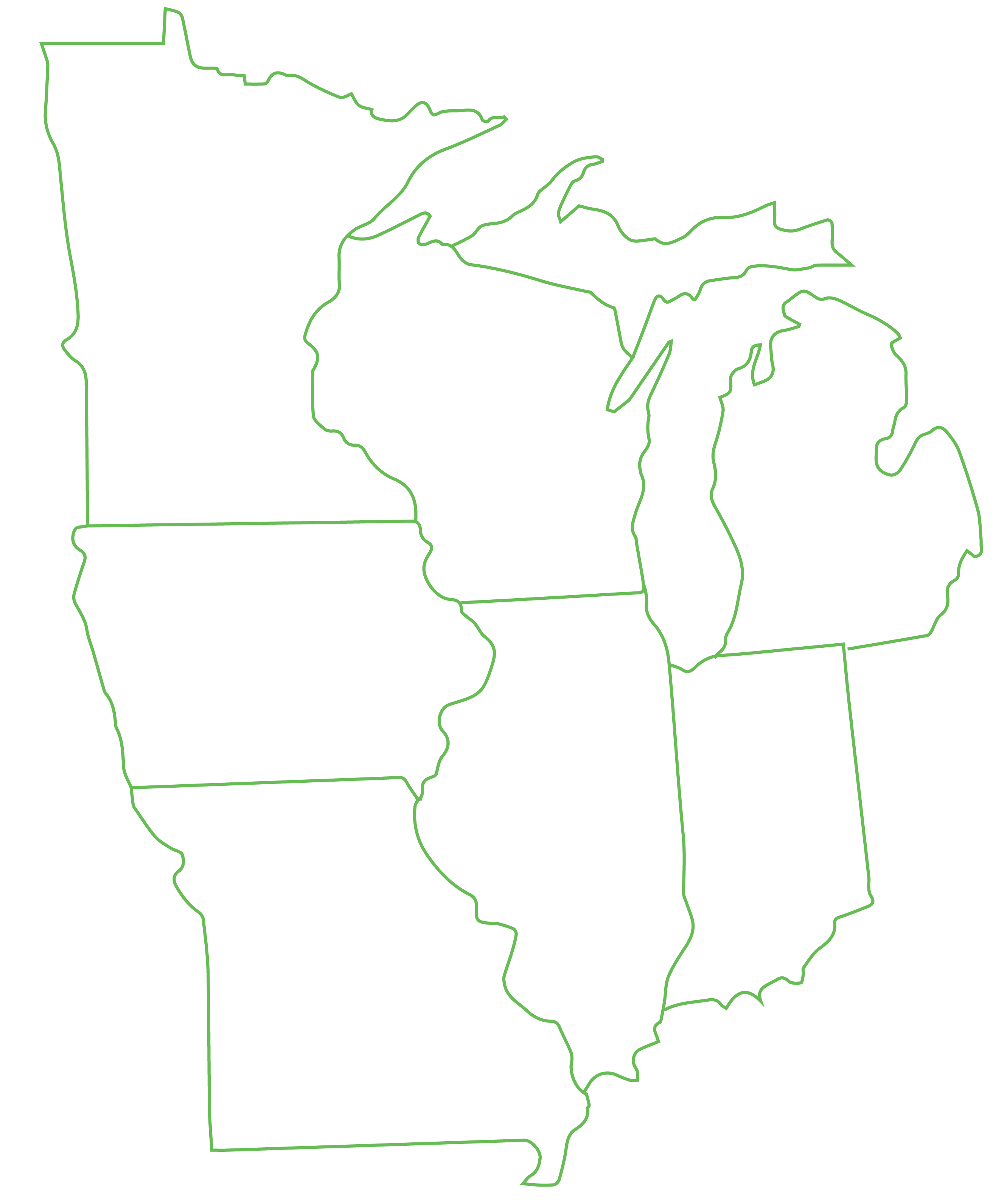

Perhaps the publishers of the MDW Atlas will take steps to mitigate the waste water they generate from making a website and publication. Massive cultural shifts that reverse the destruction of industrialization are things we all can think about and initiate. Governments, and the corporations that have purchased them, are not going to do enough to stave off the worst effects of climate breakdown. Cultural production can be called upon to do more than decorate existing power dynamics and norms. Discarding comfortable ways of doing things is more critical now than ever, and doing so in places where you are not a redundant cultural force is long overdue. Climate breakdown is coming everywhere, unevenly and brutally. Climate refugees are already moving to the Midwest from places that are on fire, using up all their water, being flooded by too much water, or seeing a future that is unlivable because of extreme temperatures. Duluth, MN, is one of the top destinations in the Midwest for internal climate refugees. Projections for the Midwest predict millions of new residents in coming decades for similar reasons. Those with the deep skills to battle climate breakdown and those who can produce new cultural forms (or want to learn) are needed outside of major metropolitan areas. Get out here and do something epic!

[1] I have written on the impact of petroleum and how it structures every aspect of your existence in the publications Petro-Subjectivity: De-Industrializing Our Sense Of Self (BKDN BKDN Press, 2015); Deep Mapping, with Nuno Sacramento (BKDN BKDN Press, 2016); and Two Ponds: Stories from the Petroleum Space-Time Continuum (BKDN BKDN Press, 2019).

[2] In 2019, we worked with the Prinzessinnengarten in Kreuzberg, Berlin to help them assess their history of work and visualize and imagine the coming 99 years of the garden’s existence. The deep mapping process is used to make these maps and to organize gatherings, and is articulated in the book Deep Mapping by Nuno Sacramento and I.

[3] Source

[4] As I write this article, we have reached 423 tons of materials composted since October 2020.

[5] Most new composters see a nearly 50% reduction in the amount of material they send to the landfill.